Teaching (tiny) LLMs to Play Text-Based Games Using RL (on a $300 GPU)

TL;DR: I trained small LLMs like GPT-2 to play text-based games using reinforcement learning (PPO) on my budget GPU. Key innovations: token-level PPO for richer signals and trie-based masking to ensure only valid actions. It worked well on with various levels of difficulty, with techniques applicable to real-world structured outputs. Code on GitHub, results show generalization, and I share lessons from the process.

Being on a career break has allowed me to focus on learning, and doing projects I like. I’ve always been fascinated by reinforcement learning, and I wanted to understand how RL applies to large language models. So I came up with this idea to teach small LLMs to play text-based games-a perfect mini-project to deepen my understanding of both RL and LLMs.

Initially, I thought this was something I could do in a week or so, but it took more like 3 weeks. The reason? I solved this without following published papers or established methodologies. I banged my head against some walls (quite a bit!), but eventually came up with a solid working solution.

My main constraint was solving this using my own PC—a $300 RTX 3060 with only 12GB of VRAM. This GPU is the cheapest 12GB Nvidia GPU available, but it’s quite slow, and the memory is a significant limitation for larger LLMs. I treated this as a challenge to write more efficient code, and I learned quite a lot about optimizing training in the process.

Code Available: The complete implementation is available on GitHub: https://github.com/NeuralPensieve/llm-textgame-rl

Understanding the Problem

Text-based games like TextWorld work like this: You’re in a situation with an objective/quest. You take an action, receive rewards based on that action, and move to the next state. It’s a perfect example of a problem that can be handled with reinforcement learning, with customizable difficulty settings.

________ ________ __ __ ________

| \| \| \ | \| \

\$$$$$$$$| $$$$$$$$| $$ | $$ \$$$$$$$$

| $$ | $$__ \$$\/ $$ | $$

| $$ | $$ \ >$$ $$ | $$

| $$ | $$$$$ / $$$$\ | $$

| $$ | $$_____ | $$ \$$\ | $$

| $$ | $$ \| $$ | $$ | $$

\$$ \$$$$$$$$ \$$ \$$ \$$

__ __ ______ _______ __ _______

| \ _ | \ / \ | \ | \ | \

| $$ / \ | $$| $$$$$$\| $$$$$$$\| $$ | $$$$$$$\

| $$/ $\| $$| $$ | $$| $$__| $$| $$ | $$ | $$

| $$ $$$\ $$| $$ | $$| $$ $$| $$ | $$ | $$

| $$ $$\$$\$$| $$ | $$| $$$$$$$\| $$ | $$ | $$

| $$$$ \$$$$| $$__/ $$| $$ | $$| $$_____ | $$__/ $$

| $$$ \$$$ \$$ $$| $$ | $$| $$ \| $$ $$

\$$ \$$ \$$$$$$ \$$ \$$ \$$$$$$$$ \$$$$$$$

Welcome to TextWorld! First step, recover the TextWorld style key from the floor

of the attic. If you can get your hands on the TextWorld style key, insert the

TextWorld style key into the TextWorld style chest in the attic's lock to unlock

it. Then, open the TextWorld style chest. Then, retrieve the key from the

TextWorld style chest. Then, doublecheck the chest within the attic is locked.

Got that? Good!

-= Attic =-

A well framed signboard tells you that you are now in the attic.

You see a closed chest. You can see a locked TextWorld style chest here. You

scan the room for a non-euclidean chest, and you find a non-euclidean chest. The

non-euclidean chest is empty! This is the worst thing that could possibly

happen, ever! You can see a rack. The rack is typical. On the rack you make out

a shadfly.

There is a TextWorld style key and a non-euclidean latchkey on the floor.

Available actions: go north, pick up TextWorld style key, look, put down TextWorld

style key, go south, examine chest

This is where you type your action, and the environment gives you a reward (typically zero until the last step), then moves to the next state.

When an LLM tries to play this game, the text above becomes the prompt. The LLM then needs to:

- Identify relevant objects

- Understand the correct sequence

- Generate syntactically valid commands that the game engine accepts

This might seem trivial for modern LLMs like Claude, and GPT-5, but for a 137M parameter GPT-2 model that was never trained on instructions, it’s a significant achievement.

What makes this challenging

Valid actions are constrained: Only specific commands work (e.g., “go north” is valid, but “go northeast” is not).

Multi-step reasoning required: Harder difficulties need 3-4 coordinated actions to complete objectives.

Sparse rewards: The model only gets meaningful positive reward (+1.0) upon quest completion, with small step penalties (-0.1) along the way.

No ground truth: Unlike supervised learning, there’s no “correct” action at each step - success is only known at episode completion.

RL is uniquely suited for these kinds of problems, where we have sequential decision making.

Understanding PPO: The Foundation

Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) has become the de facto reinforcement learning method for training LLMs, forming the backbone of techniques used in ChatGPT and Claude. Think of PPO like a coach giving feedback to improve performance-it learns from experience while being careful not to make changes that are too drastic.

PPO is an on-policy “policy gradient” method with two main phases:

1) Data Collection

- Initialize the policy (our pretrained LLM)

- Play many games using the current policy, choosing actions at every step

- Play games until completion or maximum number of steps

- Collect all experience data and pass to the PPO trainer

2) Policy Updates

- Calculate advantages at each step using rewards and value function estimates collected in the rollout

- Randomize data points and sample batches for PPO updates

- Perform multiple passes through the same data (PPO’s ratio clipping allows this)

- Update the model weights to maximize expected rewards

The key insight of PPO is the “clipping” mechanism that prevents the policy from changing too drastically in any single update, maintaining training stability.

The Core Challenge: Action Selection

This is where things get interesting. The main challenge I faced was defining how the policy should work. LLMs can only produce tokens, and if they generate freely, they won’t match any valid actions. An invalid action is equivalent to choosing the wrong action in TextWorld, and since there’s no ground truth (we only get rewards when the quest is solved), the model doesn’t learn what to produce.

Consider this simple example: available actions are ["go north", "go south", "examine door"]. If the LLM generates freely, it might produce "Your name is..." or "how do I know..." - both invalid actions that provide no learning signal.

I initially tried three different approaches to represent the policy, but all failed, typically producing low-support and peaky action distributions like 1.0 for one action or 0.6/0.4 for two actions with 0.0 for the rest. I tried various regularization methods (entropy bonuses, KL divergence penalties), but none worked. The issue wasn’t bugs-those methods were fundamentally flawed.

Solution: Constrained Generation via Trie-Based Masking

The breakthrough came with constrained generation: We represent all valid actions as a trie (prefix tree), where each path from root to leaf represents exactly one valid action—like a decision tree guiding the LLM to only possible choices.

For actions like ["examine door", "examine door knob", "go north", "go south", "look"], we build a trie:

>

├── examine

│ └── door

│ ├── EOS (complete: "examine door")

│ └── knob

│ └── EOS (complete: "examine door knob")

├── go

│ ├── north

│ │ └── EOS (complete: "go north")

│ └── south

│ └── EOS (complete: "go south")

└── look

└── EOS (complete: "look")

The generation process works as follows:

Step 1: Mask Invalid Tokens At each generation step, create a mask where valid tokens (trie children) keep their logits, while invalid tokens get -∞, making them impossible to sample.

Step 2: Sample and Advance The model samples from only valid tokens, then we move to that token’s node in the trie.

Step 3: Auto-Advance When a node has only one child, automatically follow that path until reaching either: 1) EOS (action complete), or 2) another fork (continue generation).

Example walkthrough:

- Available tokens: (

examine,go,look) → sampleexamine examinehas one childdoor→ auto-advance todoor- Available tokens: (

EOS,knob) → sampleknob knobhas one childEOS→ action complete:"examine door knob"

This approach makes invalid actions impossible-they simply don’t exist as paths in the trie. The model retains its probabilistic nature while being constrained to valid outputs only.

Token-Level PPO Implementation: A Key Technical Contribution

Here’s where my implementation differs significantly from other RL methods. Instead of treating entire actions as single decisions, I implemented token-level PPO where each token within an action sequence is treated as a separate decision point.

This means:

- Each sampled token gets its own experience entry with state, action, reward, and value

- Advantages are computed across individual tokens, not just complete actions

- The final action reward is distributed across all tokens that contributed to that action

This approach provides much richer training signal and allows the model to learn which parts of multi-token actions are most valuable. For example, in the action "examine door knob", the model learns separate value estimates for choosing "examine" vs other starting tokens, and for choosing "knob" vs EOS after "examine door".

Results and Performance

Easy problems typically required only one action to complete, while medium difficulty required 3-4 actions. The model didn’t achieve 100% accuracy, likely due to harder problem instances within each difficulty category.

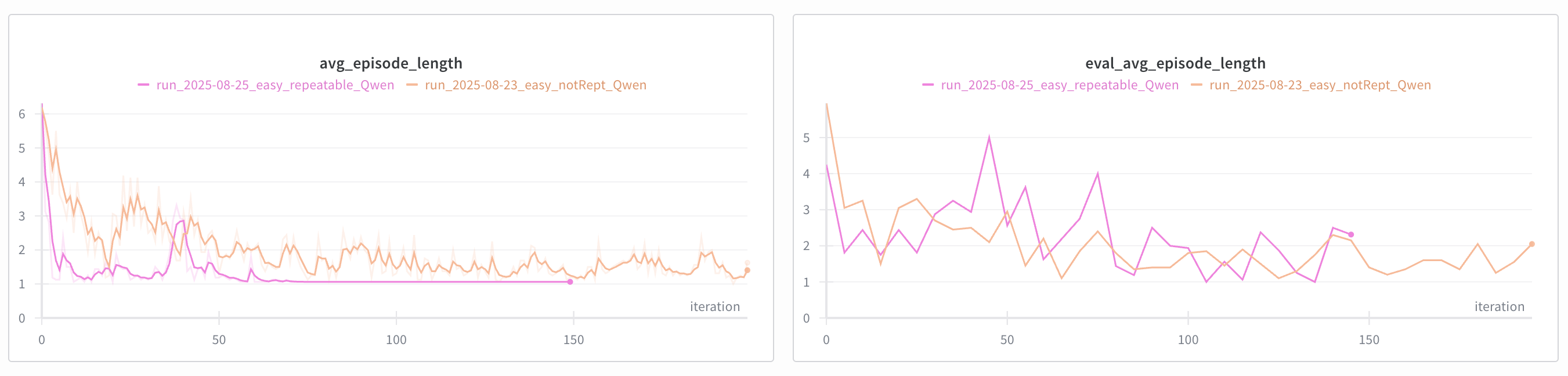

Let’s first look at easy problems:

I used repeatable environments as a test to make sure the algorithm is sound. As you can see, the model perfectly overfits those environments, resulting in avg_episode_length of 1.0. Non-repeatable environments, however, do not fully overfit but achieve very good performance of 1.5. Interestingly, the overfit model does a pretty decent job on evaluations done on randomly generated games, meaning that the model learned how to generalize based on only a handful of repeated experiences.

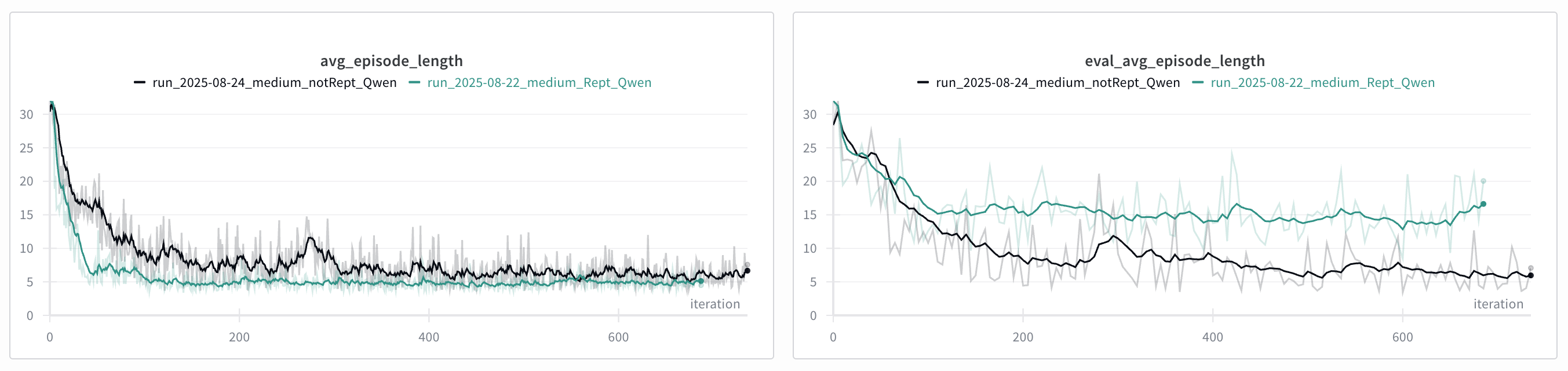

Next, let’s take a look at medium difficulty problems, which are significantly more difficult:

In the repeatable case, the model starts learning how to solve the puzzles faster, achieving lower avg_episode_length around 5 or so, but the model trained on non-repeatable environments achieves significantly lower avg_episode_length on the evaluation set. This is expected, as the model learns to extrapolate better when trained on random environments.

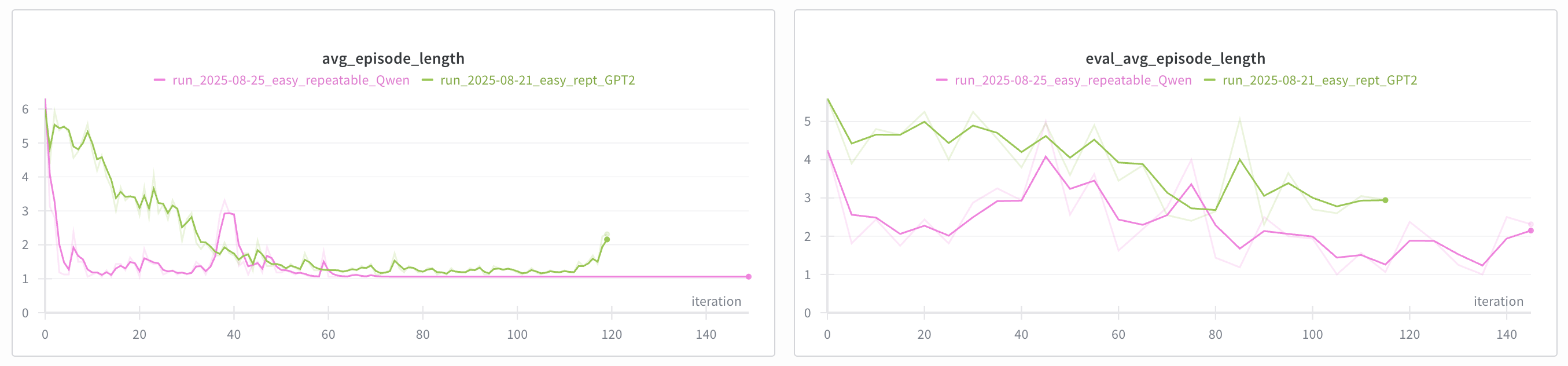

Effect of Base LLM Model

I experimented with two base models:

GPT-2 (137M parameters): More memory-friendly and faster training, sufficient for easy problems.

Qwen2.5-0.5B (500M parameters): Superior performance on harder games, trained on larger datasets with likely distillation benefits.

GPT2 allowed me to iterate faster in the beginning, not having to worry about memory too much. Qwen2.5, however, took the cake when it came to training models for harder environments. As you can see in the figure above, Qwen2.5 learned a lot faster than GPT2. I believe a much larger model would be able to be fine-tuned much faster and achieve better results. But I cannot fit and train a 7B parameter model on my GPU. Maybe methods like QLoRA would help, but in my limited experimentation, LoRA slowed down the training while not resulting in drastic VRAM usage cuts I was expecting.

Looking into Attention Layers

I was curious to know how the LLM attention layers change after the fine-tuning, so I did some visualization before and after. (The video shows attention patterns across 24 layers for pretrained vs. fine-tuned models.) I looked at all 24 layers of attention and saw some interesting patterns:

- Both models often attend to the first and last tokens in the prompt.

- Layers 0-2: No significant difference between the two models.

- Layers 3-4: The fine-tuned model starts attending to the history, but not the pretrained model.

- Layers 5-15: Nothing seems to happen in either model. Quite curious…

- Layers 16-21: The fine-tuned model starts attending to the right part of the objective, but not the pretrained model.

- Layers 22-23: Suddenly the pretrained model starts attending to a lot of tokens, but the fine-tuned model stays focused on the objective.

Beyond Games: Real-World Applications

While teaching LLMs to play text-based games might seem like a toy problem, the constrained generation techniques developed here have practical applications. Imagine using this for tasks where outputs must be strictly valid, like generating code or queries.

The most immediate use cases involve structured output generation where validity is critical: generating syntactically correct code, producing valid SQL queries, or creating properly formatted JSON/YAML configuration files. These techniques are also valuable for API integrations where LLMs must generate function calls with correct parameters and respect API constraints. In educational technology, constrained generation can guide students through valid problem-solving steps in programming tutorials or math problems, ensuring they explore within correct boundaries while learning. The common thread is situations where we need AI systems to be creative and flexible while guaranteeing outputs remain within strict formal constraints—exactly what this project achieves with the trie-based masking approach.

Lessons Learned

I’ve written extensively about challenges of deep RL before, but it’s worth mentioning some here too:

Start simple, and try to overfit Solving the simplest case of TextWorld on repeated environments, and overfitting to it, allowed me to know that my model is working. Besides, the training times were much shorter, so I could do a lot more trial and errors.

Change one thing at a time This goes without saying, but it is easier said than done. When prototyping, we often change a few things at once, and then it is not clear that the change in performance is due to which change. This is a trade-off between time/patience and gaining real insights.

Variability in RL Training: There’s significant run-to-run variability, so don’t draw conclusions too quickly. I learned to run multiple iterations initially to gauge variability, then single runs for exploration, and multiple runs for final validation.

Monitoring Multiple Metrics: I tracked episode length, win rates, entropy, action probabilities, explained variance, and various loss metrics. Understanding what to expect from each metric and how they change between runs was crucial for debugging.

The Debugging Challenge: Unlike supervised learning, RL loss values don’t directly indicate model health. Policy and value losses might decrease while performance deteriorates, and vice versa. Performance metrics are the ultimate source of truth. If these metrics are bad, there is something wrong with the model/training/hyperparameters (assuming that the metrics are correctly implemented, of course).

Collaborating with LLMs on Development

Doing this project, I used LLMs profusely, from brainstorming of the idea, to solutions, writing code, debugging, writing this blog - the whole process. It was like having a few (junior and senior) colleagues, Claude, Gemini, Grok, and ChatGPT, each having their strengths and weaknesses, and working closely with them to solve the problem. The challenge, however, was that it was not clear if you are dealing with a junior or a senior colleague! Sometimes they made amazing contributions, and other times made really bad mistakes. But I guess this is the world we live in today, and we have to adapt. But overall, I do believe LLMs sped up the process of prototyping and testing of my ideas greatly.

Here are some effective strategies that I used when working with LLMs:

- “Dueling LLMs”: I often asked one LLM for a solution, then have another critique it, and do this over and over. This often lead to refined approaches.

- Hypothesis Testing: Instead of accepting solutions blindly, I often asked LLMs to write debug code to test their hypotheses.

- Code Review: I always diffed LLM-generated code with existing code to understand changes, and questioned back when needed.

One last thing is a few words of caution about using LLMs.

- Be the driver When developing a large project, you cannot trust an LLM to do the right thing. You need to make sure you understand all the code they generate.

- Don’t always believe them LLMs these days are really powerful, but that doesn’t mean they know what they are talking about, and sadly, they still can’t say they don’t know. This sometimes leads to a behavior akin to “gaslighting”, when you repeatedly push back on their findings. Once, they even tried to convince me the issue is deep down in GPU/CUDA, and there is nothing I can do about it, but that was just not true, and the issue was within my code.

- Don’t abandon good software practices As an example, I had this really complicated monolith logic of rollout collection using constrained decoding, and I asked an LLM to refactor it. I went through a lot of vetting and dueling of ideas, before I let it to rewrite it. It did, and at the surface it looked great, but it would not run. It turns out when you ask LLMs to refactor, they discretely change the logic as they see fit as well. So I had to scratch that, and start from writing unit tests for this complicated logic, and of course asked LLMs to do that. Once I became confident that the tests have good coverage, then I asked them to refactor, and went through many debugging to finally make sure the two codes are identical in logic.

But overall, I am more than happy that we can use these powerful tools to speed up our work, and increase our productivity. I am delighted that I don’t have to sift through stackoverflow and GitHub to find answers to my problems and bugs, and I love the fact that they can write boiler-plate code much faster and better than I can do.

Conclusion

This project demonstrated that sophisticated RL techniques can work on modest hardware with careful optimization and engineering. The key contributions were:

- Token-level PPO implementation providing richer training signal

- Constrained generation via trie-based masking solving the action validity problem

- Comprehensive diagnostic framework for debugging complex RL training issues

- Memory optimization techniques enabling larger model training on consumer hardware

The success of teaching small LLMs to play text-based games opens up interesting possibilities for applying RL to language models in resource-constrained environments. The techniques developed here could be valuable for other structured text generation tasks requiring adherence to complex constraints.

Appendix

In this section, I go more into some of the details of the implementation. If you are not an RL/LLM practitioner, you may stop reading.

Hyperparameter Configuration

The final hyperparameters that worked well:

Learning rates:

- Model: 1e-5 (cosine decay to 1e-7)

- Value head: 1e-4 (separate learning rate crucial for stability)

PPO specific:

- Clip ratio (ε): 0.2

- GAE lambda: 0.95

- Discount factor (γ): 0.99

- PPO epochs: 4

- Batch size: 2 with 32 accumulation steps (effective batch size: 64)

Key discoveries:

- Value loss coefficient: 0.05 (reduced from 2.0 - critical for preventing harmful value function)

- Entropy coefficient: 0.01 (maintains exploration without dominating gradients)

- Temperature decay: 0.995 (from 1.0 to 0.5 minimum)

Environment settings:

- Easy: 8 max steps, 100 iterations

- Medium: 32 max steps, 1000 iterations

- Parallel environments: 16 for training, and evaluation

Sophisticated Experience Collection Architecture

The heart of the project was the experience collection. Managing multiple parallel environments while handling token-level generation required a sophisticated setup. The system handles:

Parallel Environment Management:

- Runs multiple TextWorld games simultaneously for efficient data collection

- Maintains separate tries for each environment’s valid actions

- Coordinates token generation across all active environments

- Handles environment completion at different rates

Multi-Modal Operation:

- Training rollouts with temperature-based sampling

- Evaluation runs with greedy (temperature=0) selection

- Detailed logging for sample games during evaluation

State Management:

- Tracks partial action generation across multiple tokens

- Maintains episode statistics and game logs

- Handles episode termination due to completion vs. step limits

- Proper cleanup and resource management

This parallel architecture significantly improved sample efficiency compared to sequential environment execution.

Advanced Memory Optimization Techniques

Training even small LLMs on a $300 GPU required aggressive memory optimization:

8-bit Optimizer: Using bitsandbytes.optim.AdamW8bit reduces optimizer state memory by 75%, freeing 2-3GB of VRAM.

Gradient Accumulation: Process 2 samples 32 times to achieve effective batch size of 64 with minimal memory overhead, though it increases time.

Gradient Checkpointing: Recompute activations during backward pass, cutting memory by ~60% at ~30% slower training cost.

Mixed-Precision Training: FP16 for forward, FP32 for gradients, nearly doubling trainable model size with loss scaling for stability.

Flash Attention: For Qwen, reduces attention memory from O(n²) to O(n), allowing longer sequences and 15-20% faster training.

Smart Context Management: Dynamically truncate history while preserving key state, using importance scores to remove least relevant parts.

Explicit Memory Management: Call torch.cuda.empty_cache() and gc.collect() after iterations to recover 500MB-1GB.

These allowed training a 500M parameter model with PPO on 12GB VRAM.

Comprehensive Diagnostics System

Standard RL debugging is notoriously difficult because loss values don’t directly indicate performance. I implemented extensive diagnostics:

Value Function Health Monitoring:

- Explained variance:

1 - Var(returns - values) / Var(returns) - Correlation between predicted values and actual returns

- Value prediction bias and range analysis

- Terminal state prediction accuracy

Training Progress Indicators:

- Episode completion rates and average lengths

- Action probability distributions and entropy

- Gradient norms and learning rate schedules

- Sample efficiency metrics

Reward Signal Analysis:

- Reward distribution statistics

- Percentage of non-zero rewards

- Terminal vs. intermediate reward patterns

This diagnostic framework was crucial for identifying issues like harmful value functions and training instabilities.

State Representation and Reward Design

I carefully designed the state representation to include:

- The current objective/quest description

- History of past interactions and actions (configurable length)

- Current environment description

- Notably: Available actions were NOT included in the state - the model learns what’s possible through the constrained generation process

For rewards, I used a simple but effective scheme:

- +1.0 for winning the game

- -0.1 step penalty for each action taken

This encourages both winning and efficiency, with maximum possible reward being 1.0 minus the minimum steps required.

Value Function Debugging: A Technical Deep Dive

One of the most frustrating debugging experiences in this project involved the value function actively sabotaging training. For more than a week, I watched my model’s performance suffer despite what seemed like reasonable loss curves. The breakthrough came when I started monitoring a metric I’d initially overlooked: explained variance.

This metric tells you how well your value function predicts actual returns. Positive values mean it’s helping, negative values mean it’s worse than useless. Mine was consistently negative - the value function was literally worse than predicting a constant.

As an experiment, I disabled the value function entirely (just returning zeros), and performance immediately improved. This was counterintuitive - actor-critic methods supposedly benefit from value functions to reduce variance. But in my case, the critic was actively misleading the actor.

Through systematic debugging, I uncovered three critical issues:

The value loss was dominating training. I’d set the coefficient to 2.0, following some papers without considering my specific problem. When the value function is wrong (which it always is initially), this high coefficient meant the model spent most of its capacity trying to predict values rather than learning good actions. Dropping it to 0.05 fixed this - just enough signal to learn values without overwhelming the policy gradient.

Initialization mattered more than expected. With random initialization, my value head was predicting +1.9 for all states, while actual returns averaged -0.3 (due to step penalties). This massive bias took thousands of iterations to correct. I fixed this by initializing near-zero with a -0.1 bias matching the expected step penalty.

Gradient interference was not helpful. The value head was backpropagating gradients through the shared LLM backbone, essentially telling the language model to change its representations to make value prediction easier. By detaching the hidden states before the value head, I stopped this interference while still allowing the value function to learn from the LLM’s representations.

The lesson here extends beyond this specific problem: in actor-critic methods, a poorly configured value function doesn’t just fail to help - it actively hurts. Unlike supervised learning where bad auxiliary losses might slow convergence, in RL a misleading value function provides wrong advantage estimates that push your policy in the wrong direction. Always monitor explained variance, and don’t hesitate to disable the value function entirely as a debugging step.